System cameras and the the future - is it mirror-less?

Two interchangeable lens cameras with the same sensor size, one has a reflex mirror and one doesn't

Mirrors in cameras have played a crucial part in photography over the years as integral parts of both twin lens reflex (TLR) and single lens reflex (SLR) cameras. The first single lens reflex (SLR) cameras were made in the 1880s. These were large and cumbersome cameras using large format films. Smaller SLRs arrived in the 1920s and the first 35mm SLR cameras came to market in the 1930s. So has the 130 year old concept of the SLR run its course?

This article revolves around the supposition that a reflex mirror camera design, fundamental to today's DSLR cameras, is one that is out of date. Sooner or later the expense and disadvantages of mirror-based SLR cameras will force camera makers to embrace new technologies to make less bulky and cheaper to manufacture, potentially more reliable, and more versatile system cameras that do away with the mirror-based reflex design. And there is already plenty of evidence to support this in the form of the Compact System Camera (CSC).

By far the fastest growing segment of the camera market is the compact system camera. These are cameras that can use interchangeable lenses like a DSLR, but there is no reflex mirror and pentaprism or pentamirror optical viewfinder. CSCs have been developed to fill the gap between high end compacts, including superzoom bridge cameras, and DSLRs, but the argument goes that the concept of a CSC and the technologies they have spawned may ultimately replace the DSLR in a scaled-up form. If this happens, there could be a revolution in the system camera industry and it's likely to be controversial among those who will end up resisting change..

The Contax S, in 1949 this was the first single lens reflex camera with an eye-level viewfinder that used a pentaprism.

What's wrong with a mirror?

For camera and lens designers, the space occupied by a reflex mirror between the back end of the lens and the film or sensor plane is a headache. For a start, it makes the depth of the camera relatively large, but more significantly it forces the design of lenses to be bigger and bulkier than they might otherwise be, especially for medium and wide angle lenses. With these lenses the optics have to work harder to focus the light onto the film frame or sensor area. Camera makers who have already started to produce lenses for compact system cameras, where there is no mirror box, have demonstrated dramatic reductions in the sizes of lenses that have the same optical specification as equivalent SLR lenses.

The insides of a typical digital SLR. Note the reflex mirror that has to swing up and out of the way of the rear of the lens when the exposure is made, and the five-sided pentamirror.

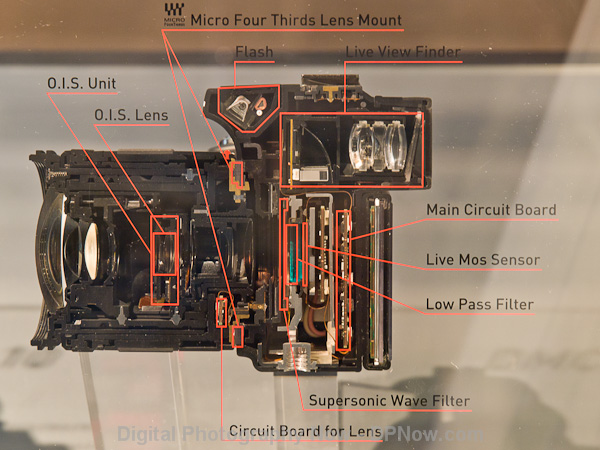

And this is the inside of a mirrorless interchangeable lens camera with a similar specification to the DSLR pictured before.

Now compare the two cameras side by side - the mirrorless camera on the right, and its lens, are significantly more compact and lighter than the DSLR on the left.

Quick-return reflex mirror mechanisms are very complex and delicate and in modern DSLRs. There is usually a secondary mirror that diverts light for the autofocus system. These mirrors are attached to delicate hinged mechanisms that are spring loaded and motor-driven and must maintain a very precise orientation. Besides the mirror, there is also a focus screen and a pentamirror or pentaprism that directs the lens image to the eye-level optical viewfinder. The system is vulnerable to dust and dirt and mis-calibration. It's also linked to extra mechanisms, light metering and autofocus sensors. By eliminating a mirror a substantial segment of the build cost of a camera disappears too.

So a mirrorless system camera is smaller, lighter and cheaper to make. So why aren't we all using them?

What do you lose when you ditch the mirror?

Is the end of the SLR mirror nigh?

The viewfinder question

Perhaps the key allure of an SLR is the purity of its optical viewfinder. Many DSLR photographers can't imaging life without this. If you lose the mirror you will have to rely on an electronic framing aid of some description. We're already familiar with LCD screens on the back of compact cameras as well as DSLRs that provide a 'live view' of what the camera lens sees, but there is no getting away from the fact that a mirrorless camera - and even some types of mirrored DSLR camera variants like the Sony Alpha SLT range, - will force you to use an electronic viewfinder.

Autofocus

Since the first autofocus SLRs appeared thirty years ago, autofocus has become very sophisticated. Professional DSLR models, especially, can track and maintain focus on fast moving subjects very reliably, something mirrorless cameras can't yet claim, although one manufacturer does claim that its mirrorless CSC will focus faster on stationary subjects faster than any DSLR. Low light focus reliability is better on DSLRs too.

Responsiveness

Theoretically, SLRs should be more responsive to the shutter release. On a mirrorless camera the shutter stays open most of the time while feeding the live view on your screen or electronic viewfinder. When you fire the shutter, it first has to close fully before opening and closing to make the exposure. In practice this doesn't seem to be a real-world issue, but on paper it's a deficiency.

Size - smaller is not always better

One thing that CSCs have almost exclusively aimed for is a smaller and smaller form factor. A good number of DSLR users I have discussed the phenomenon of the mirrorless system camera with point out that for their personal preferences, a CSC is simply too small. People with large hands and fingers and those who wish to use bigger and heavier lenses will not be persuaded by the current crop of CSCs. And there are no professionally-orientated models with dust and moisture sealing and fast shooting, with longer lasting batteries and portrait grips. But let's not lose sight of the argument in favour of mirrorless system cameras - photographers, including professionals, using DSLRs do want kit bags that are less bulky and back-breaking and so smaller and lighter cameras and lenses will be welcome, but not at the expense of handling, functionality, and image quality. Mirrorless cameras will, eventually be able to meet all three requirements in a smaller and lighter form, the question is simply - when?

Change

Finally, although you could simply persevere with a camera that has an empty space where the mirror used to be, logic dictates that going mirrorless would mean building a new system from the ground upwards to gain full benefit of the mirrorless architecture. That means photographers would have to invest in a new system. Ouch!

And what do you gain by not having a mirror?

Both these lenses have exactly the same optical specifications - 7-14mm f/4.0 zoom lenses and they are both designed to work with the same size sensor. The reason why the one on the right is so much smaller is because the mirrorless camera system it works with brings the lens 2cm closer to the sensor.

We have already covered the fact that camera systems designed to be mirrorless can mean smaller, lighter, and cheaper to manufacture cameras, as well as smaller and lighter lenses. The elimination of an intricate and delicate reflex mirror mechanism should also mean better reliability, as well as less vibration and noise. But there are other benefits too.

Sophisticated information overlays

A live view display means that your viewfinder can be information-rich. We are already seeing visual aids overlaid to indicate settings in a context-sensitive manner, real-time preview of colour, exposure, special effects, and even depth of field without having to peer at a darkened view. The view can be zoomed for critical focus, too. Some cameras let you choose the focus point very precisely in the live view and even let you vary the size of the focus point visually, something completely unthinkable with conventional DSLR autofocus systems. You can also review your shots in the viewfinder instead of the external screen when required, which can be an advantage in bright conditions.

Electronic viewfinders also show a 100% view of the frame, and the good quality ones display a good sized view compared to some medium and smaller sensor DSLRs. Movie recording can be performed with a live view through the viewfinder; on a DSLR the viewfinder goes dark when recording. EVFs are a lot better than they used to be, with the current leading models displaying 1.4 million dots, or 480K pixels. That's ten times the resolution of most camera LCD screens of just 2-3 years ago. EVF technology is still developing fast and they are only going to get better.

Focus accuracy and reliability

Focus accuracy is much better with mirrorless cameras. What I mean is that when the camera determines focus, it should be 100% correct because the imaging sensor is used for focus, the same sensor that takes the picture. On an SLR the focus sensor is completely separate and must be carefully calibrated at the factory. Focusing woes caused by mis-calibrated cameras and even lenses are a perennial danger for demanding photographers using SLRs. Exposure accuracy and white balance is theoretically better with mirrorless cameras, again because the main imaging sensor is used rather than a separate one.

Less legacy compromise

Also, as mirrorless systems are completely new and legacy-free, there is little or no compromise. A good example of this is with autofocus. Video recording was not even considered a potential use for SLRs, so lenses were designed for still camera focusing requirements only. DSLRs with movie recording functionality either don't provide AF during movie recording or if they do it tends to be too jumpy or too slow. It's a similar issue with focusing with live view; DSLR lenses are not optimised for live view AF. Mirrorless cameras now usually offer relatively sophisticated AF for both still and movie modes.

Compatibility with old lenses

An interesting bonus of mirrorless cameras that we are already witnessing with CSCs is the ability to fit just about any legacy lens to the camera via an adapter of some description. This is made much easier because of the reduced distance of the lens mount from a mirrorless camera to its sensor - and the absence of a mirror that might otherwise whack the end of the lens.

How about the best of both worlds?

Sony's SLT Alpha 55 - it has a (fixed) mirror but this is not a DSLR.

Sony has introduced a variant of its Alpha DSLR called a SLT (single lens translucent). The word 'translucent' refers to a semi-silvered fixed mirror that lets 70% of the light from the lens to the viewfinder and 30% to the autofocus sensor. This means that the advantages of a DSLR-style autofocus system can be retained and full performance compatibility with Alpha system DSLRs is preserved. But these cameras don't have an optical reflex viewfinder - they are not DSLRs. Instead they have electronic viewfinders. A bonus of not having to electro-mechanically operate a swinging mirror is that the shutter can be fired faster in continuous bursts without resorting to even more expensive mirror mechanics. The Sony Alpha SLT-55, for example, is by far the cheapest system camera that can shoot at 10 frames per second. And as there is no interruption to AF system during shooting, the focus sensor can keep doing its thing while the camera is snapping away at 10fps.

Sony's SLT solution is clever and interesting, but it is undeniably a half way house. On the one hand it denies the photographer that cherished optical viewfinder, and does not benefit from the possibility of much smaller and lighter bodies and lenses afforded by a true mirrorless camera system. And while the SLT system means there is no need to change your Alpha system lenses, and I wonder if those lenses will work with smooth and subtle focus transitions while recording movies? The main benefits are the reduction in mechanical complexity and some lowering of manufacturing cost, plus no need to change you lens system, and very high-speed shooting at a relatively low cost.

So what is the future for system cameras?

CSCs to overtake DSLRs but not replace them?

Some analysts are predicting that the compact system camera market could overtake the DSLR market within 5 years. It's certainly growing fast (doubling year on year at present) while the DSLR market is fairly flat. But let's not forget that CSCs are not actually designed to compete directly with DSLRs. The CSC market is projected to be bigger than the DSLR market, but not necessarily replacing it. The concept of a smaller and lighter mirrorless system camera is actually aimed at compact users who don't want a big, heavy, and complicated DSLR.

Interestingly, DSLR users have been attracted to CSCs. Some DSLR users fit the target criteria for CSCs perfectly, except they bought DSLRs because there was no alternative at the time. These photographers are now trading their DSLRs in for CSC systems. Other DSLR users are buying CSCs to complement their DSLRs, especially where a degree of compatibility is available that means they can use their lenses on both types of camera using an adapter. The DSLR is used for certain types of work and the CSC for portability when travelling light, for example.

CSCs don't yet address a replacement for DSLRs

So far, however, none of the mirrorless camera makers has addressed the interests of DSLR users who want more than a CSC can offer them in the form of a larger, more professionally specified, design.

The two dominant DSLR makes, Canon and Nikon, have not declared any major interest in producing CSCs. They have their existing markets to protect. On the other hand, statements made by both companies without any fanfare have suggested that they are keeping an eye on the development of CSCs.

Meanwhile, Sony, Samsung, Olympus and Panasonic, all of whom have struggled in the DSLR stakes, have forged ahead with CSCs. Pentax, another DSLR minnow, has also launched an ultra compact CSC. At present, Sony appears to be highly committed to its commercially very successful NEX CSC range while maintaining investment in the Alpha DSLR line. But Sony has found it hard to meet targets to beat Nikon or Canon in the DSLR market. This has forced the company to innovate, and one result is the Alpha SLT, a DSLR-like camera that is compatible with Sony Alpha DSLR lenses but uses and electronic viewfinder.

Panasonic had a go at the DSLR market and quickly realised it had to develop an alternative, and can be credited with creating the CSC with the creation of the Micro Four Thirds system, which is now also patronised by Olympus. Much speculation surrounds Olympus' commitment to its Four Thirds format E-System DSLR range as it has committed almost all its efforts into becoming an established CSC player with its Micro Four Thirds Pen range. Samsung won't say as much, but it does look like its short alliance with Pentax in DSLRs finished some time ago and now all in-house resources are committed to its NX CSC range.

Are you getting the warning signs? Mirrorless cameras don't appear to be healthy for the long term future of DSLRs. If CSCs really take off and start to erode the DSLR market instead of just complementing them, Canon and Nikon must surely be forced to join the party - and where would that leave their DSLR systems?

There is the argument that CSCs are not designed to replace DSLRs and that's a perfectly justifiable argument. But eventually the technologies developed for ever smaller and lighter CSCs will eventually find its way into a different kind of mirrorless camera that will be marketed as a direct DSLR alternative.

One thing I am sure of is that we are just at the beginning of a long and possibly controversial debate about the future of system cameras in the light of the emergence of mirrorless system cameras.

Reader feedback:

Discuss this story:

What is an SLR?

The Nikon D7000 is a typical enthusiast photographer's choice of DSLR camera today

Before the SLR was invented, the only way a photographer could see exactly what the camera lens was seeing was to remove the film and replace it with a ground glass plate onto which the lens projected its image. Not only was this upside-down, it was also dim and so you had to view it with a cloth over your head! These cameras were large and bulky and hardly useful for anything but static subjects.

As cameras became smaller, photographers had to depend on external framing aids, varying from a simple wire target rectangle to an optical system that worked in parallel with the camera's lens. This was fine until you wanted to frame a subject close up and parallax errors became severe, so framing became inaccurate.

A cut-away showing the inside of a modern DSLR

The ingenious solution was the SLR. This placed a mirror behind the lens, diverting the image it projected from the film to a ground glass screen. Instantly you could see exactly what the lens was seeing. The only problem was that you had to make the mirror get out of the way of the camera's shutter and the film when it was time to take the picture. Early SLRs had a spring-loaded mirror connected to the shutter release. Once the shutter button was pressed, the hinged mirror was released and it swung upwards and the shutter was fired. The only problem then was that the mirror stayed up and the viewfinder remained dark until the mirror was manually re-deployed, usually by advancing the film to the next frame!

When you look through the viewfinder the mirror diverts the light projected from the lens to the reflex viewfinder system above.

When the exposure is made the mirror must flip up and out of the way of the light from the lens. This stops the viewfinder from working until the exposure is completed and the mirror flips back down again.

Later SLRs introduced the quick return mirror, which meant - as you are now probably familiar with, the mirror swung back immediately after the exposure had been made, so your view through the finder was only interrupted during the actual exposure. Also, to provide a more natural view through an eye-level viewfinder at the back of the camera rather than peering downwards at a horizontal screen, the pentaprism viewfinder was introduced and is housed in the familiar SLR 'hump' on the top of most SLR cameras.

This stage in the evolution of the SLR was completed in the 1950s. The next stage was to integrate light metering. At first this was accomplished with an external selenium cell arrangement. Later, internal meters were introduced so the light through the lens (TTL) was measured. At first this simply indicated the exposure variance via a needle in the viewfinder and you had to close the lens aperture to make a reading. Later we had 'open aperture' metering, without the need to stop the lens down and darken the view. Eventually, the metering became linked to the aperture and/or shutter and we had automatic TTL metering and exposure.

The first autofocus Canon DSLR was the EOS-650, launched in 1987, two years after Minolta launched their Maxxum 7000 (also known as Dynax in some markets), which was the first SLR camera with an integrated autofocus system.

In 1981 the first autofocus SLR was launched by Pentax, but this was basically an ordinary film SLR mated to a lens that had its own autofocus mechanism. Minolta and Canon were the first to really grasp the mettle with integrated autofocus and Canon, especially, with its new EOS SLR system produced a non-legacy solution with excellent AF performance. SLR AF systems use a range-finding system. There are two focus sensors for each focus point and as long as there is enough brightness and contrast the system can compare the phase of each from each sensor and so determine which way the focus needs to be directed and even by how much. This is called phase-detect autofocus. The system also determines how the motor that controls focus in the lens is geared. The system has been around for almost three decades and is now highly refined.

In the late 1990s manufacturers started to modify existing SLR models, replacing the film aspects with digital imaging sensors. Kodak worked with both Canon and Nikon in developing such cameras mainly for press photographers. They were crude and cumbersome, with huge battery packs and ridiculously low resolution (1.5 megapixels to start with) sensors. But by 1999 some more recognisable DSLRs were beginning to appear, like the 2.7MP Nikon D1, and the 3MP Canon EOS-D30. In 2003 Olympus introduced the first and only mainstream DSLR system designed from the ground up, the E-System, of which the first model was the E-1. This was also the basis for the Four Thirds initiative, which Panasonic Lumix and even Leica joined in 2006. Also in 2003 Pentax finally entered the DSLR race with its curiously named *istD cameras. Konica Minolta released their first DSLR in 2004, which was later to be acquired by Sony as the Alpha system.

The rise of the CSC

The Micro Four Thirds Panasonic Lumix DMC-G1 was introduced in 2008 and was the first Compact System Camera. It shared the same size sensor as the Four Thirds Olympus E-3 DSLR pictured with it here.

Compact System Camera arrived in September 2008, when Panasonic Lumix unveiled the DMC-G1, the first Micro Four Thirds system camera. It looked like a mini DSLR and it used interchangeable lenses. But instead of a reflex mirror and prism optical viewfinder, there was a high resolution electronic viewfinder fed by the same sensor that records the actual photograph. Panasonic decided to make this leap after it tried, and failed, to get established in the DSLR market with cameras based on Olympus' Four Thirds DSLR system. Panasonic decided to use much of the Four Thirds system specifications, including the sensor size and key lens/body electronic communications protocols, so it was relatively easy to provide adapters for older Four Thirds lenses.

Without a mirror box, Panasonic moved the lens mount 2cm closer to the sensor. This had two dramatic impacts. First of all it made the camera body considerably less deep, enabling a really compact form factor. But it also enabled lenses to be designed to be much more compact, too, especially mid focal length and wide angle lenses. This is because the longer distance of the lens from the sensor plane in SLRs, to accommodate the mirror box, is far from optically ideal. The closer the lens can be situated to the sensor, the less powerful and less massive the glass of the optics need to be.

This is also important when it comes to focusing. Without the ability to use a phase-detect autofocus arrangement, which depends on the mirror in an SLR, the sensor itself has to be used to determine focus. This is done by measuring the contrast at the focus point. If the contrast increases, this indicates that the focus travel direction is correct. If contrast reduces, the lens is moving away from correct focus. Once the ideal focus has been exceeded the contrast starts to decrease. When this is detected the lens has to back-track to the point of best contrast and so - focus. In simple terms this main image sensor autofocus system, or contrast detect AF, stops and starts the lens many times during a focus action. To enable adequate speed the moving mass of the glass elements inside the lens has to be as low as possible. The gearing of the focus motors also needs to be different.

Olympus followed Panasonic into Compact System Cameras with the retro-style Pen range, compatible with Panasonic's G-series Micro Four Thirds platform, itself developed from Olympus' Four Thirds DSLR platform.

In the case of Micro Four Thirds, although the system retained backwards compatibility with a lot of the body to lens protocols, two additional electronic connections were added to enable improved control over the focus electronics. Panasonic, and Olympus - who followed Panasonic in to Micro Four Thirds almost a year after the G1 was launched, have been steadily improving their focus systems and Olympus now even claims its latest CSC cameras have a single action focus speed that is better than any DSLR. Continuous AF performance for following fast moving subjects is still inferior to DSLRs, but let's just remember that DSLRs have had 30 years to develop phase detect autofocus while CSCs have barely had 3 years to develop contrast detect autofocus.

Samsung very quickly followed Panasonic's lead and introduced its own Compact System Camera platform, called NX, in late 2010.

Samsung was the next manufacturer to enter the CSC market early in 2010 with the NX-10. Although Samsung had previously developed DSLRs with Pentax and shared the Pentax K-mount, oddly Samsung developed a completely new lens mount for the NX system that shared no electrical compatibility with the K-mount. But Samsung did use the same 14MP APS-C CMOS sensor that it developed for the GX-20 and Pentax K-20D DSLRs. This brings the benefit of good sensor performance, being relatively large compared to the Four Thirds format sensor being used by Panasonic and Olympus, but means that Samsung NX lenses are physically larger than comparable Micro Four Thirds lenses.

Sony joined the Compact System Camera Party mid-way through 2010 with the radical-looking NEX system.

Sony joined the CSC party back in May 2010, when it introduced the NEX-5 and NEX-3. Like Samsung, Sony decided to use the relatively large APS-C sensor developed for DSLRs. Again, this means NEX lenses are big and bulky compared to comparable Micro Four Thirds lenses, so to compensate Sony made the NEX camera bodies especially small. The striking and unusual design was a huge hit, especially in Japan, where Sony immediately went to the CSC number one position despite a mixed reception from journalists who didn't like the user interface or handling of the NEX range.

The diminutive Pentax Q is, on paper at least, a Compact System Camera, but its very small sensor size makes it a very different proposition to other CSCs.

Pentax is the latest manufacturer to develop a new CSC platform, called 'Q'. Pentax has gone completely the other way from Samsung and Sony and developed a camera around a much smaller sensor than Micro Four Thirds. This means Pentax Q cameras are very small and light, as are Q lenses. In fact the Q system is so compact, it's arguably not competing directly with the other more-established CSCs.

While the current impetus in CSC design has been to make smaller and smaller designs, there is no doubt that the development of CSC technologies will eventually find their way in to larger and more sophisticated camera models that will be pitched directly against DSLRs.